One striking feature of Nigeria’s current economic debate is the ease with which large figures are circulated—and the even greater ease with which they are misassembled. Tax revenues are casually added to oil receipts; oil receipts are counted again under customs collections or so-called “subsidy savings”; borrowing is treated as income; and the resulting totals are presented as evidence of incompetence or theft.

This is not economic analysis. It is arithmetic illusion.

At the heart of most viral critiques of Tinubunomics lies a failure to distinguish between revenue, cash, and financing, as well as between federation-wide collections and actual federal budgetary resources. These distinctions are not technical footnotes; they are the foundation of public finance.

Revenue is not the same as cash available to the Federal Government. Borrowing is not income; it is financing that creates future obligations. Federation receipts are not synonymous with what the Federal Government can spend. Once these fundamentals are ignored, any dramatic number can be manufactured.

The pattern is familiar. Aggregate tax collections are cited, often correctly, in gross terms. Oil revenues are then added without clarifying whether they are gross or net, whether costs and deductions have been removed, or whether they represent federation-wide or federally retained income. Customs receipts are layered on, sometimes without acknowledging that they are already embedded in non-oil revenue figures. Borrowing is then added as if it were free money, followed by “subsidy savings,” as though eliminating a fiscal leak automatically creates a pool of idle cash.

The outcome is a sensational headline—₦150 trillion, ₦170 trillion, ₦180 trillion—followed by the question: where did the money go?

The answer is simple: much of it never existed in the form being implied.

Subsidy reform, for example, does not generate instant discretionary cash. It closes a hole. Under the old system, underpricing created arrears, opaque netting arrangements, and quasi-fiscal obligations. Reform first eliminates these hidden drains. Any fiscal benefit emerges gradually through reduced deficit pressure, improved budget discipline, and more targeted support—not through an overnight windfall.

Debt figures are equally misunderstood. A large share of the recent increase in Nigeria’s debt stock, when measured in naira terms, reflects exchange-rate revaluation of existing external obligations, not fresh borrowing. When the exchange rate adjusts, the naira value of dollar-denominated debt rises automatically. Treating this accounting effect as new borrowing is a category error, not an economic insight.

Most persistently, federation-wide collections are portrayed as if they belong entirely to the Federal Government. They do not. In a federation, revenues are shared, earmarked, netted, and statutorily allocated. Federal fiscal reality is determined by retained revenue plus deficit financing—not by gross inflows aggregated for political effect.

Tinubunomics was never a promise of instant abundance. It is a macro-fiscal reset undertaken under severe constraints: inherited debt service, FX realism, security spending, legacy arrears, and constitutional obligations. Its logic is structural—restoring price signals, strengthening revenue administration, rebuilding credibility, and repricing the public balance sheet while protecting the most vulnerable.

Those who insist on treating national finance like a household ledger will always find scandal where none exists. But accountability does not begin with viral arithmetic. It begins with audit logic.

The proper way to assess government performance is straightforward: examine federally retained revenue; separate it clearly from financing; track spending across debt service, personnel, capital, and transfers; and then evaluate outcomes—roads built, power delivered, rail extended, schools and clinics rehabilitated.

Anything else is not scrutiny. It is theatre. And no amount of theatrical arithmetic can substitute for fiscal discipline.

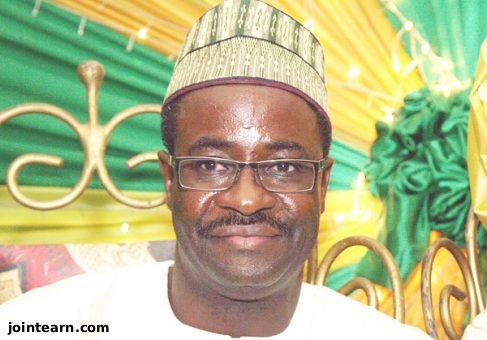

Yakubu is the Director-General of the Budget Office of the Federation.

Leave a Reply