South Korean police have launched a sweeping crackdown on citizens accused of participating in Cambodia-based online scam operations, seeking arrest warrants for 58 of 64 nationals recently deported from the Southeast Asian nation.

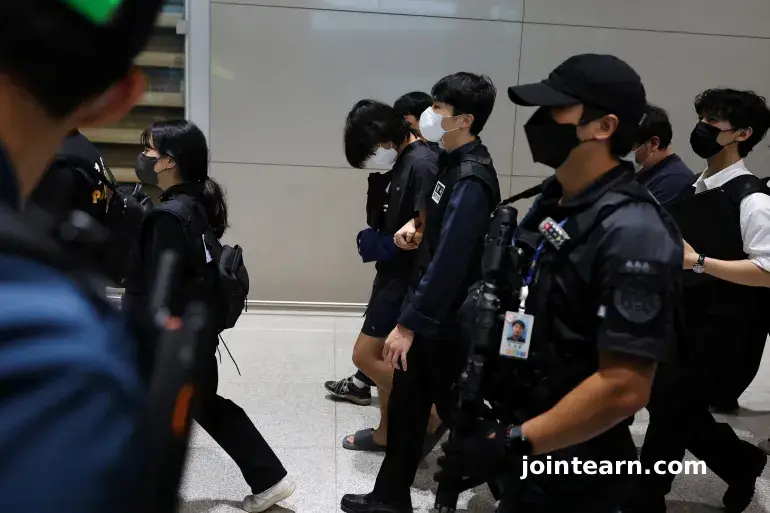

The National Police Agency in Seoul confirmed on Monday that it has requested court approval to detain the suspects, who arrived in South Korea over the weekend following a coordinated repatriation effort.

Officials said one individual was immediately taken into custody, while five others were released pending further investigation. The detainees are alleged to have been involved in “pig butchering” scams — a form of online fraud that combines elements of human trafficking, psychological manipulation, and cryptocurrency crime.

‘Pig Butchering’: A Global Fraud Phenomenon

The term “pig butchering” refers to the process of scammers “fattening up” victims through fake romantic or business relationships before swindling them out of large sums of money. The method, which originated in China, has spread rapidly across Southeast Asia, with Cambodia, Myanmar, and Laos emerging as key hubs for the illicit trade.

Victims are often lured through dating apps or social media platforms and convinced to invest in fraudulent cryptocurrency platforms controlled by criminal syndicates.

In many cases, the perpetrators themselves are trafficked workers, trapped in scam compounds after being promised legitimate jobs abroad.

“Those held in these facilities are often subjected to forced labor, physical abuse, and psychological coercion,” said Park Sung-joo, head of South Korea’s National Office of Investigation, describing the repatriated suspects as being linked to voice phishing, romance scams, and crypto investment fraud.

Seoul’s Expanding Crackdown

South Korean authorities estimate that around 1,000 South Koreans may currently be operating within Cambodian scam centres, either voluntarily or under duress.

National Security Adviser Wi Sung-lac said that the repatriated group includes “both willing participants and individuals forced to work against their will,” underscoring the blurred line between perpetrators and victims in the global scam ecosystem.

The mass deportation follows a high-profile diplomatic intervention last week, when Seoul dispatched a delegation — led by the deputy foreign minister and including law enforcement and intelligence officials — to Phnom Penh to coordinate action against scam networks.

The move came amid public outrage over the killing of a South Korean college student in Cambodia, whose death in August was linked to a criminal ring operating out of one of the country’s scam compounds. The student’s murder, reportedly involving torture, sparked protests and prompted calls for tighter travel restrictions and stronger protection for South Korean nationals abroad.

New Travel Bans and Regional Cooperation

In response, the South Korean government imposed a partial travel ban on certain Cambodian provinces known for housing scam centres. Authorities also announced plans to establish a joint investigative task force with regional partners to monitor cross-border trafficking and cyber fraud activities.

“Protecting our citizens from being exploited or coerced into criminal operations is now a top national security priority,” Wi said.

The crackdown aligns with a broader international push to dismantle transnational cybercrime networks in Southeast Asia.

Just last week, the United States and United Kingdom imposed coordinated sanctions against the Prince Group, a powerful Cambodia-based conglomerate accused of running a vast web of scam centres across the region. The group’s operations, according to U.S. investigators, involve money laundering, human trafficking, and large-scale cryptocurrency fraud.

U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi described the sanctions as “one of the most significant strikes ever against the global scourge of cyber-enabled financial fraud and human trafficking.”

Regional Ripples and Japan’s Response

The Cambodian scam industry, which flourished after the COVID-19 pandemic forced casinos and hotels to pivot to illegal online operations, is now facing mounting international scrutiny.

On Friday, Japan’s public broadcaster NHK reported that Tokyo police had arrested three people in connection with similar scams linked to Cambodia, signaling that East Asian governments are now coordinating responses to the transnational threat.

Security analysts say the trend illustrates how cyber-enabled human trafficking has evolved into one of the fastest-growing criminal industries in the world, blending elements of digital fraud, organized crime, and modern slavery.

Modern Slavery Behind the Screens

Investigations by rights groups and journalists have revealed that many scam centres in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar operate like slave labor camps, where victims — often from China, Vietnam, and the Philippines — are confined, beaten, or electrocuted if they fail to meet fraud quotas.

Human Rights Watch has described these compounds as “digital sweatshops of deception,” generating billions of dollars annually in illicit profits.

South Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs said it is working with Cambodian authorities to identify victims of trafficking among the deportees and ensure they receive humanitarian assistance and rehabilitation support.

Ongoing Legal Battle

While most of the repatriated suspects face charges of fraud and violating South Korea’s Act on the Aggravated Punishment of Specific Economic Crimes, investigators have not ruled out pursuing human trafficking or organized crime charges against ringleaders operating within Cambodia and neighboring countries.

Police have also requested cooperation from Interpol and ASEAN law enforcement agencies to track down financiers and digital infrastructure operators behind the scams.

A Warning for Potential Victims

Authorities warn that criminal syndicates continue to lure young people through fake job offers promising high salaries in Southeast Asia. Victims often find their passports confiscated upon arrival, leaving them stranded and trapped in coercive working conditions.

“Anyone considering overseas employment should verify recruitment agencies through official government channels,” a spokesperson from the Korean National Police Agency (KNPA) said.

The KNPA added that it plans to expand cybercrime education campaigns and enhance digital surveillance to intercept online recruitment ads linked to trafficking networks.

Leave a Reply